A closer look at links between environment and security

Caux Dialogue on Environment and Security 2020

19/07/2021

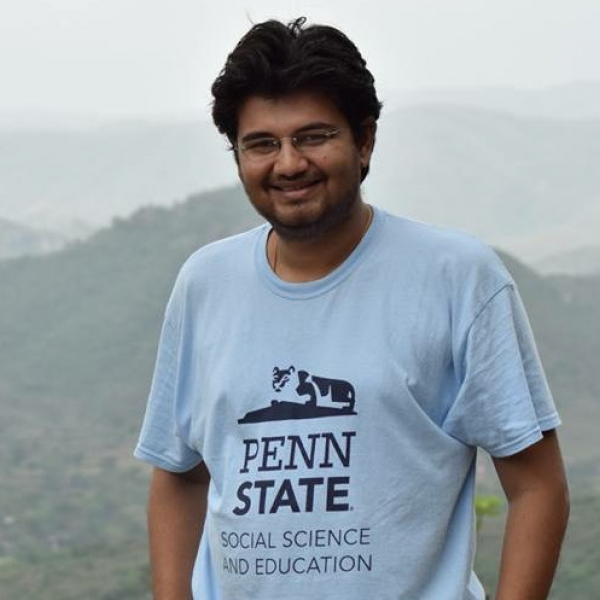

Food security is a key to understanding the complex connection between climate and security, Dhanasree Jayaram, Assistant Professor in the Department of Geopolitics and International Relations Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE), told this year’s Caux Dialogue on Environment and Security (CDES). Jayaram, who is also Co-Coordinator of MAHE’s Centre for Climate Studies, has been part of CDES since the inaugural Summer Academy on Land, Security and Climate in 2019. This year she addressed the plenary on ‘Climate Finance: catalyst of holistic solutions’.

Environmental shifts often have most impact on economies that are heavily dependent on agriculture, Dhanasree Jayaram explained, saying that ‘Food security is interconnected with livelihood and employment security of the farmers.’ For example, she said, the public system in Nepal puts too much emphasis on rice in its food-supply strategies. Rice is a water-heavy crop, so attempts to use it as a primary food source lead to overextraction of water, creating drought-like situations and a ‘lopsided’ policy in an already-vulnerable population.

One of the reasons problems of food security are difficult to resolve, Jayaram said, is the lack of understanding and academic research on the issue. Another knowledge gap is the influence of violent conflict, whose connection to environmental degradation is under-researched. Jayaram believes the solution must be ‘structurally driven’, because such an approach puts ‘less burden on the individuals who are the most vulnerable and have the least access to resources’. Farmers, who ‘work enough to meet their ends’, cannot automatically be expected to get involved.

A structurally driven approach would come from large institutions, such as the United Nations and the World Bank, but also from start-ups with the resources to contribute and help communities closer to the ground. Plenty of individual action is already taking place, Jayaram said, but structural problems keep ‘large-scale actors and actions on the sidelines and [put] too much burden on individual people’. As an example she cited the gaps in how institutional resources are allocated, which can make it difficult for communities to use them effectively to adapt and transform their systems. This is one area where institutions can get involved: by trying to understand what the gaps are, and bridge them, for a better allocation of resources.

The African Development Bank is using several models to address the gap, including calls for proposals specifically for small-scale projects from civil society organizations and NGOs, said Gareth Phillips, Manager of the Bank’s Climate and Environment Finance Division. These calls are issued by the Bank’s growing Climate Change Fund. The Bank has also launched the Adaptation Benefit Mechanism, which will be ‘accessible for small-scale, context-specific adaptation projects’ developed by community-based groups. Its goal is to certify the environmental, social and economic benefits of transformative adaptation to climate change, by de-risking and incentivizing such investments.

Food security and transformative adaptation are only some of the ways to examine security in the context of environmental degradation, with many possible connections existing that can be researched and understood to resolve the difficult cases that exist Nepal and other agriculturally-dependent economies. However, until these connections are still not fully understood and integrated institutionally, so we must now turn to individuals to address these areas in research and bring them to wider attention.

You would like to participate at this year's edition of the Caux Dialogue on Environment and Security?

REGISTER NOW

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Watch the replay of the plenary on ‘Climate Finance: catalyst of holistic solutions’: