Europe: A Mindset of Diversity

By Mary Lean

30/04/2024

Spanish journalist Victoria Martín de la Torre is passionate about Europe, diversity and interfaith relations. After 15 years as press officer of the Socialists and Democrats group in the European Parliament, and with two books under her belt, she now works at the research service of the European Parliament, which provides academic studies to the Members of the European Parliament, and is currently completing a doctorate on what the post-World War II pioneers of the European Union could teach Europe today.

As a case study, Victoria chose the former Caux Initiatives of Change Young Ambassadors Programme, an intensive training programme for young Europeans who aspire to take an active role in transforming society, with the aim to equip them with the reflective and practical tools to build sustainable change, inspire deeper conviction about Europe and connect them to a supportive network of similarly engaged young people.

When the EU started out, it was known as the European Community, Victoria points out. She explains that the founding fathers drew their definition of ‘community’ from the writings of the 13th century theologian and philosopher, St Thomas Aquinas.

‘Aquinas said that in a community all members are free to participate. They are equal, they give up their self-interest and they look for the common good. He also said that the common interest is much more than the sum of the individual interests of the member states.’ This definition of the common interest appears in the treaties which created the European Community.

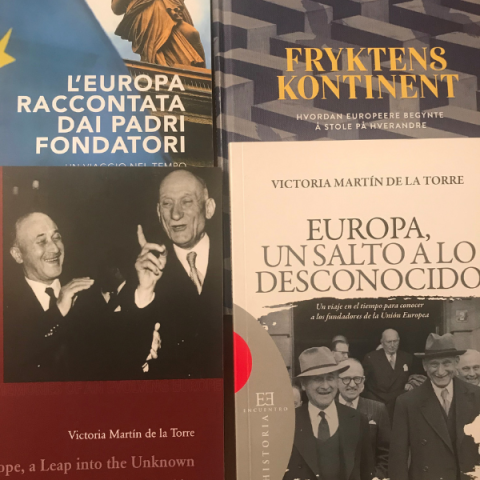

of Victoria's book "Europe, a leap into the unknown"

about the EU founding fathers

There are legal and institutional models for European integration, Victoria says, but the founding fathers maintained that you can only build community if ordinary people come together. ‘Robert Schuman, the French politician and one of the EU’s founding fathers, said that Europe is not a geographical concept, it’s a mindset. This mindset means accepting difference. That’s why I think intercultural dialogue is so important.’

For her doctorate, she chose three programmes against which to test her theory that intercultural dialogue builds community: Caux’s Young Ambassadors Programme (2015 – 2021) which brought together young Europeans to explore the connection between personal and global change; Belieforama, a network of small NGOs which offers training to overcome anti-Semitism and Islamophobia by addressing stereotypes and prejudices; and Anti-Rumour Strategy, promoted by city halls in different countries and by the EU, which combats prejudice towards migrants.

Victoria discovered that all three programmes see human beings as relational and each of them creates an atmosphere where connection happens. ‘If you remove the obstacles, human beings are designed to connect’, she says, but points out that the question remained what happens when people go back home.

When Victoria interviewed participants and facilitators from the three programmes, she not only found commonalities but also surprises: ‘Most people said that the projects had planted a seed in them, so that in the future, when they have a spontaneous reaction of fear or prejudice, they can work on it. I expected that the key would be the lasting friendships people had built, but not everyone had kept up their friendships. The awareness was the most important thing.’

She asked participants whether the programmes had made them more willing to have friends from another group. ‘At least half of them said no – perhaps because people who apply to such programmes are already open to meeting the other anyway. But they all felt that they had a responsibility to be multipliers of the process they had experienced, even if only around their family and friends.’

When Victoria took part in the conference Addressing Europe’s Unfinished Business at Caux in 2016, her highpoint was the small so-called community groups which met for moments of quiet reflection and sharing. ‘This was what made me connect most with other participants. I love Initiatives of Change and its principle that change starts with oneself.’

Looking at her personal experience, she was surprised when respondents said that the information and knowledge they had gained was as important as the human connections: ‘Even if you connect at a human level, you may still have some misconceptions. If you don’t address the issues, the connection stays at a very superficial level. Mind and heart should go together.’

You can only build community if ordinary people come together. (...) Europe is not a geographical concept, it’s a mindset. This mindset means accepting difference. That’s why I think intercultural dialogue is so important.

Victoria’s passion for intercultural exchange dates back to ‘the best year of her life’, as a 23-year-old Masters student in New York. After growing up in a ‘mainstream’ Spanish family in Madrid, she found herself studying with classmates from all over the world. ‘My five best friends were Jewish, Muslim and Christian.

At the time she did not believe in God, but these friendships made her reconsider: ‘I was not sure which religion to choose, so I got involved in interfaith dialogue.’ Today she is a committed Catholic, and in 2009 founded the Abraham Forum for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue, based in Madrid.

Victoria can’t help but feel that with the shift of name from European Community to European Union in 1992 something has been lost: ‘For a lot of people, it became an economic project instead of a community.’ But she is convinced that the experience of Covid has done something to reset this: people in Europe realized that they needed each other and fears that other countries would follow the UK’s Brexit example have not materialized so far.

At the same time, she worries about the growth of nationalism and negative attitudes towards migrants. ‘There is a lot of talk in the EU about European citizenship and citizens’ rights. That’s fine. But what about those among us who are not citizens? The migrants who come by boat from Africa are not going to vote or pay taxes, at least for the time being. But that does not mean that they are not persons. I don’t think you can have a real European Community according to the founding fathers if it’s only for citizens. It has to be for people.’

I don’t think you can have a real European Community according to the founding fathers if it’s only for citizens. It has to be for people.

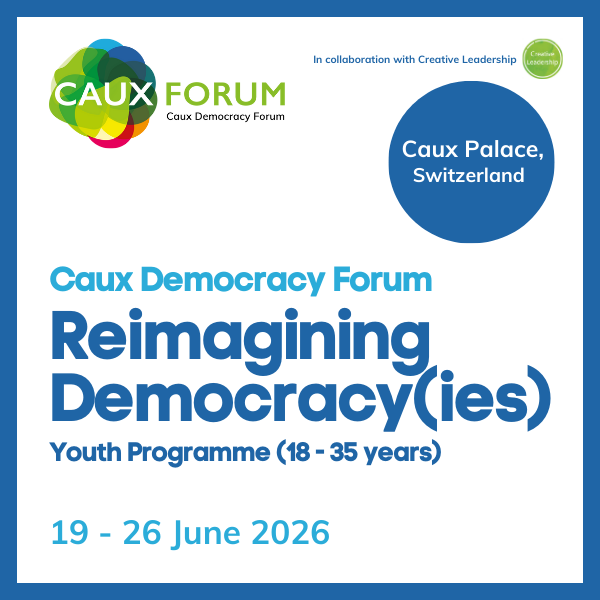

Democracy is currently retreating across the world. If the tide is to turn, those of us who live in democracies have a vital role to play. Democracy cannot be implemented from outside, and each society needs to develop their way of enabling governance by the people for the people. But whatever its form, this depends on an educated citizenry, just governance, an inclusive economy and truthful media.

This summer, the Caux Democracy Forum (15 – 19 July, 2024) will explore the question how democracy can be revitalised across Europe and the world.

Join us in July and become part of a global community of changemakers at the Caux Democracy Forum!

Find out more and register here:

- OPENING CEREMONY: Revitalising Democracy – Towards Inclusive and Peaceful Societies : 15 July, 2024

- FULL RESIDENTIAL CAUX DEMOCRACY FORUM : 15 – 19 July, 2024