1964: Daw Nyein Tha – ‘When I point my finger at my neighbour’

By Mary Lean

19/05/2021

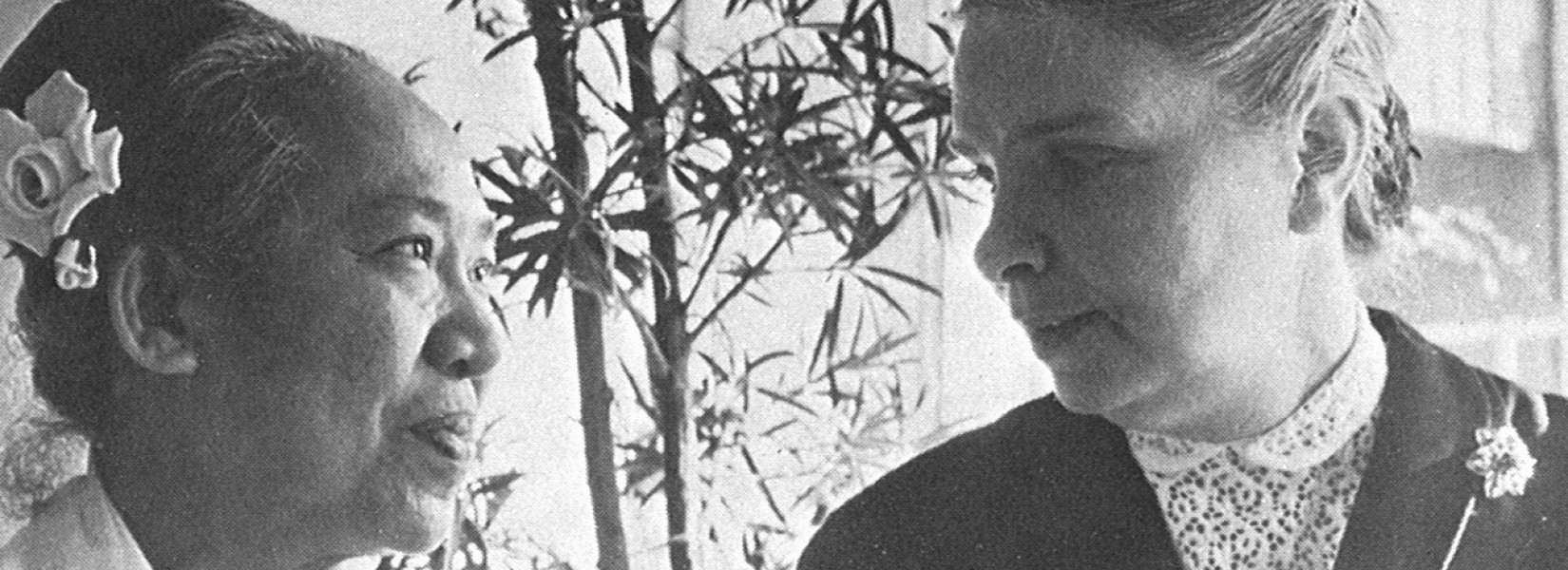

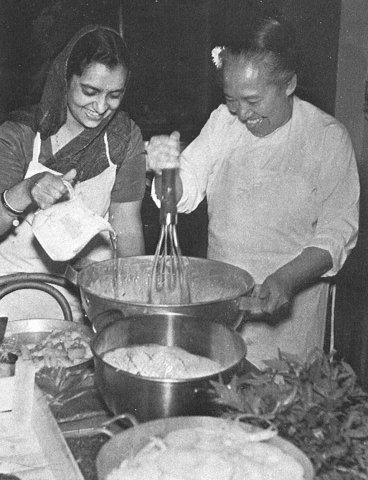

You never knew who you might meet in the Caux kitchens in the 1960s. The kitchen which prepared dishes for Asian guests was presided over by a small Burmese woman in her 60s. Few would have guessed that she was a former headmistress from Myanmar (then Burma) and a friend of Mahatma Gandhi.

Daw Nyein Tha – or ‘Ma Mi’, as her family and friends called her – became the youngest headmistress in Myanmar in 1921, aged 21. Her style was authoritarian. After 10 years, her staff and pupils finally rebelled when, as the Christian head of a Christian school, she refused to allow the Buddhist girls to observe a religious fast day. The incident caused a national furore.

Now I knew why Christ had put me in the school – not just to be headmistress but to learn to love people.

The issue was finally resolved when she accepted that she disliked the girls and that her pride and conceit made it hard for the teachers to work with her. She apologized publicly. ‘Now I knew why Christ had put me in the school – not just to be headmistress but to learn to love people,’ she said later.

This lesson stayed with her throughout her life, as she moved away from teaching and into work for reconciliation and justice both at home and around the world. She first encountered Moral Re-Armament (now Initiatives of Change) on a visit to Britain in 1932 and embraced its message of inner listening and starting with yourself.

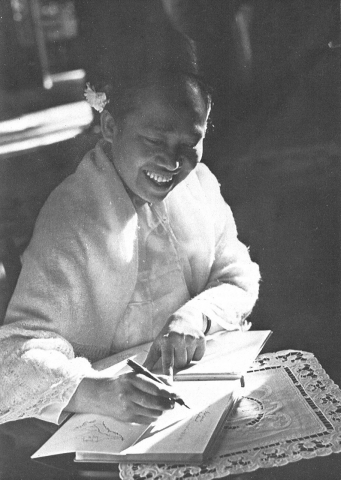

Wherever she was, Daw Nyein Tha remained a teacher – often using her hands to convey her truth. She liked to demonstrate a Burmese proverb: ‘When I point my finger at my neighbour, there are three more pointing back at me.’ The phrase became one of MRA’s best known songs, written by Cecil Broadhurst for the musical Jotham Valley and made famous by the Colwell Brothers. (Listen to the song here)

When she visited Mahatma Gandhi in his ashram in 1941, she used a handkerchief pulled taut between two hands to show the tension between two people who each insist on having their way. When one hand stops pulling, the other also has to yield and they can work together. ‘Yes,’ responded Gandhi mischievously. ‘It works very well with a handkerchief, but does it work with people?’

In Thailand in the early 1950s, she used a hollowed-out seed containing three tiny ivory elephants to make her point. Thailand and Burma had nursed a smouldering enmity ever since the Burmese destroyed Thailand’s ancient capital and stole its prized white elephants 200 years earlier. These memories rankled in Thailand, but had been largely forgotten in Burma. Now the Burmese airforce, chasing Burmese rebels, had bombed Thai border villages and feelings ran high.

At a meeting with the Thai prime minister, Daw Nyein Tha emptied the three ivory elephants into his palm. ‘These little elephants have been away from Thailand for such a long time,’ she said. ‘They were so homesick, they have got very thin.’ The Prime Minister laughed, and the story went out on the radio. Later the Burmese Prime Minister apologized to the people of Thailand on Burma’s behalf and backed this up with financial compensation.

Daw Nyein Tha spent most of the last years of her life in Britain and Switzerland, unable to return to Myanmar, then under military dictatorship.

She taught those who worked with her in the Asian kitchen at Caux some simple principles, as Marjory Procter writes in her biography The World My Country: ‘It was the people for whom you cooked that mattered…. Why you were cooking was more important than what you were cooking.’

Asked by an Italian journalist what someone like her was doing cooking, Daw Nyein Tha replied, ‘I am not cooking. I am obeying God.’

It was the people for whom you cooked that mattered…. Why you were cooking was more important than what you were cooking.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

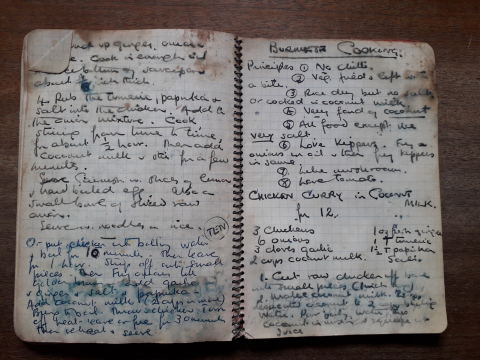

Some time during this period, my mother helped in the Asian and African kitchen at Caux. She wrote the recipes she learnt, including ‘Daw Nyein Tha’s prawn curry’, in a small notebook. She also jotted down some ‘principles of Asian cooking’ – starting with the sweeping generalization that ‘no one east of Burma likes lamb’ and continuing with the essential components of a curry meal: ‘something hot and something mild; something dry and something wet; something sour and something fried; some sort of bread’. I still have the notebook, stained and blotched from use, as my mother offered a taste of home to foreign students in Oxford, where we lived.

Mary Lean, United Kingdom

You can read more on Daw Nyein Tha here:

- Joyful Revolutionary, Harry.S. Addison, Friends of MRA, 1969

- The World My Country, by Marjory Proctor, Grosvenor Books, 1976

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Watch an extract of this film from our archives (1950) showing a Burmese group with Daw Nyein Tha (05'57", first woman on the left, front row)

Watch Daw Nyein Tha speaking to three women in the film Ma Mi from Burma from our archives.

______________________________________________________________________________________

This story is part of our series 75 Years of Stories about individuals who found new direction and inspiration through Caux, one for each year from 1946 to 2021. If you know a story appropriate for this series, please do pass on your ideas by email to John Bond or Yara Zhgeib. If you would like to know more about the early years of Initiatives of Change and the conference centre in Caux please click here and visit the platform For A New World.

- Video Buchman 1948 archive: Initiatives of Change

- Video Ma Mi from Burma: Initiatives of Change

- Photo teaser: Joyful Revolutionary, R.D. Mathur on behalf of Friends of Moral Re-Armament (India), 1969

- Photos: The World My Country, by Marjory Proctor, Grosvenor Books, 1976