1960 - Cyprus: 'Hope never dies'

By Andrew Stallybrass

06/05/2021

There are few problems in the world that have not found some echo in the conferences and encounters in Caux since 1946. In 1960 Cyprus gained its independence, after several years of sometimes violent conflict between its Greek and Turkish communities and its British rulers. The first flag of the new republic to go overseas officially was sent to Caux by the President, Archbishop Makarios, and raised there on Independence Day, 16 August.

This gift was a tribute to the quiet work of people from Moral Re-Armament (MRA, now Initiatives of Change) in the wings of the negotiations between Britain and the different parties to the conflict: the Greek Cypriot majority, most of whom wanted enosis (union with Greece); the Turkish minority who wanted a partition of the island to guarantee their rights; Greece and Turkey.

British soldiers in the background

In 1954, Archbishop Makarios, who was both the religious and the political leader of the Greek community, had stayed in MRA’s London centre, before being sent into exile by the British two years later.

A leading Turkish editor and journalist, Ahmet Emin Yalman, had been in Caux in 1946, and used his pen to try to bring the communities together. In 1958, Yalman wrote in an article widely circulated in the Greek media, ‘Cyprus is not meant to be the point of division. It is meant to be the bridge of understanding.’ Connections facilitated by MRA played a part in the compromise agreement signed in London in March 1959 by Makarios, who was elected President in 1960.

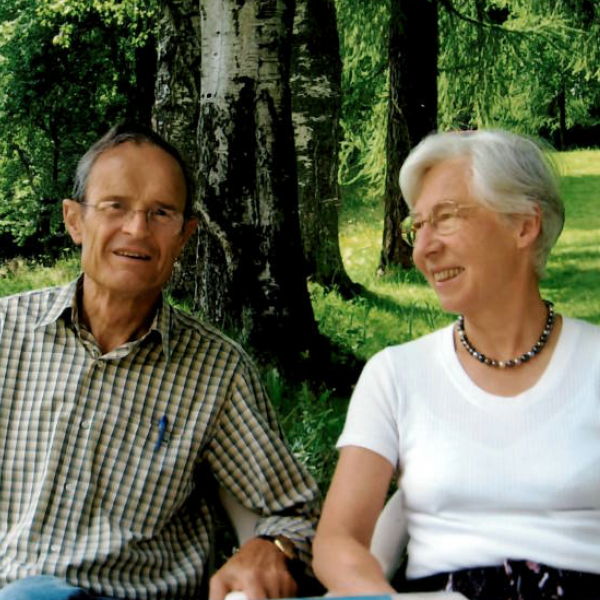

In 1959, two Swiss MRA workers got married, and, in early 1960, left Caux in a minibus, to support the growing work of MRA in Cyprus. Marcel and Theri Grandy had planned to stay in Cyprus for three months, but, as Marcel wrote later, stayed for ‘three extraordinary decades’. Over the years they made countless visits to Greece, Turkey and Lebanon, showed MRA films, hosted visiting groups with plays and musicals, and organized delegations to Caux.

What we didn't know then was that three months in Cyprus would become three extraordinary decades.

‘Theri and I arrived in a country that was at boiling point,’ wrote Marcel. In this environment, so Theri, they had to adjust to ‘life as a couple, a whole new culture in the Mediterranean, an extremely busy, though unplanned, schedule, and living in a small MRA community made up of some quite high-spirited younger people’. Every day Cypriots came to their home with gifts: oranges, potatoes, celery, invitations to their homes and villages, offers of car-rides and even a live chicken. There were many from both communites who hoped to heal their island’s wounds.

After independence, communal tensions continued, despite many efforts towards trust-building. In 1974 there was a coup against Makarios, led by supporters of Greece’s right-wing military regime who wanted union with Greece. This provoked an invasion by Turkey, and a de-facto division of Cyprus. Perhaps a third of its inhabitants became refugees in their own country.

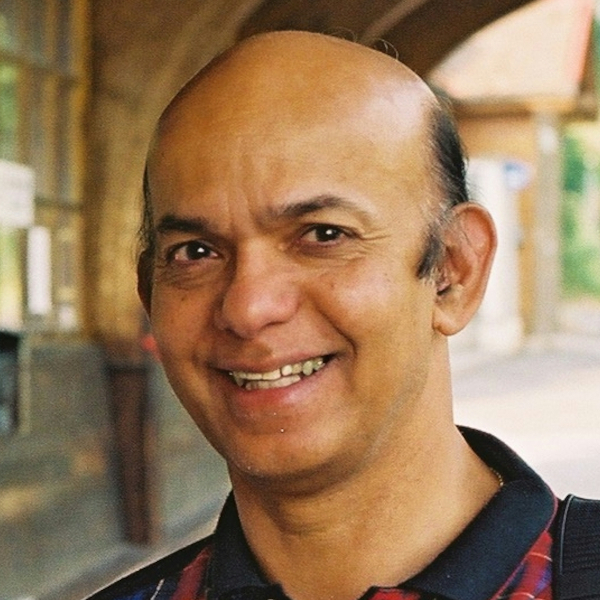

Through the years since, Cypriots have continued to work to break down barriers, build trust and fight corruption. One of these is Spiros Stephou, who first went to Caux in December 1960, as a young customs official in the port of Famagusta.

He had been a member of the Greek guerrilla movement, EOKA, in the 1950s, planting bombs in the port with the aim of driving the British out of Cyprus. His wife, Maroulla, worked with him, but despaired of his gambling and drinking.

At Caux, Spiros seemed more interested in the bar near the conference centre than the meetings. But on the plane home, a realization hit him: ‘If I continue with my chaotic life, I will destroy not only my life but also the life of my island.’

Over the next months, he built a new relationship with Maroulla, told his boss about the goods he had stolen in customs, and slowly paid off his debts. He became known for his stand against corruption and ended his career as Deputy Director of Customs.

If I continue with my chaotic life, I will destroy not only my life but also the life of my island.

Cyprus’s division continues today, despite fruitless efforts by the United Nations and others to bring a lasting solution. After his last visit to Cyprus, three years before his death in 2006, Marcel wrote: ‘The situation in Cyprus is far from promising. Yet as we talked and renewed our friendships fresh rays of hope became evident. We know how difficult it is in a politically stagnant situation to keep hope and belief alive. But, as we ourselves have known, and as so many of our friends have experienced, with a change of motivation and direction in a person’s life, hope never dies.’

Marcel and Theri Grandy left Cyprus after Marcel was asked to become President of Initiatives of Change Switzerland. He held this post for ten years, from 1989 to 1999.

____________________________________________________________________

Watch the video from our archives of the celebration of Cyprus Independance Day in Caux, 1960

____________________________________________________________________

This story is part of our series 75 Years of Stories about individuals who found new direction and inspiration through Caux, one for each year from 1946 to 2021. If you know a story appropriate for this series, please do pass on your ideas by email to John Bond or Yara Zhgeib. If you would like to know more about the early years of Initiatives of Change and the conference centre in Caux please click here and visit the platform For A New World.

- Video Cyprus Independance Day at Caux: Initiatives of Change

- Cyprus 1959-1960: An unfinished story, Daniel Dommel, Caux Books, 1998

- Photos and quotes: Hope never dies: the Grandy story, Virginia Wigan, Caux Books, 2005