The role of journalists in a country at war

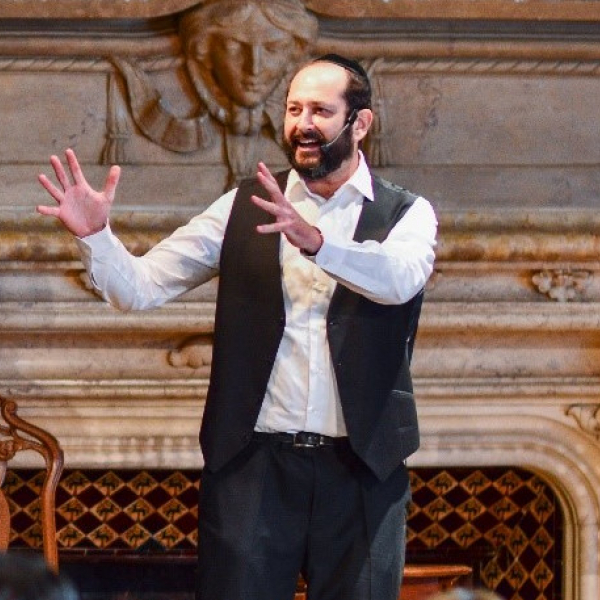

Addressing Europe's Unfinished Business 2018

27/07/2018What is the role of a journalist in a country at war? With many of his compatriots thinking that journalists should be information warriors, finding the answer to this question is an everyday struggle for Ukrainian journalist Oleksiy Matsuka. ‘Some of our readers expect us to defend our country. But we want to protect our independence as journalists. How can we make sure we don’t fall prey to propaganda as journalists in the middle of a war? How do we keep presenting information without bias?’

This summer Oleksiy Matsuka was one of a group of journalists from Ukraine who met in Caux during the conference Addressing Europe’s Unfinished Business to discuss these questions. Matsuka is the founder of the Donetsk Institute of Information, an NGO whose mission is to disseminate independent news about the Donbass region through different media channels and analyse other news from the region. They also organize the yearly Donbas Media Forum, which brings together hundreds of Ukrainian media professionals to discuss the challenges of covering the ongoing conflict in the region. Both the Institute and Matsuka now operate from Slovyansk, a city just outside the occupied territory.

This was Matsuka’s third visit to Caux having first participated in 2016. He recounts how his time in Caux has helped him in the process of reflecting on his contribution to peace in his country. ‘The first step to solving a problem is to start with yourself,’ he says. For him, this meant acknowledging the trauma the war had left him with when he had to flee his home and move to the controlled area. ‘After my initial patriotic reaction to the war, I learned to recognize this trauma. However, I had to keep it separate from my work as a journalist in order to maintain my professional standards.’

Matsuka is convinced that professional journalism can contribute to the process of peace. ‘We don’t go to the front line to fight but we can disseminate unbiased information and ask the questions that need to be asked.’ Matsuka explains how he changed his tone as a journalist from the affirmative to the interrogative, and how this was met with resistance. ‘People here expect journalists to state facts, not to ask questions but asking questions is of the utmost importance especially when working in a conflict.’

Through their reporting Matsuka and his colleagues try to reduce the polarized news landscape. ‘Our actions should, at the very least, avoid making the situation worse than it is now.’ The Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe adopted rules for media in conflict and the reporters of the Donetsk Institute of Information work according to this conflict sensitive reporting. For example, when speaking about the uncontrolled area, they never use the word terrorist. ‘Terrorist is a toxic word. There are 2 million people living in the uncontrolled territory and they are not terrorists.’ Instead they might say ‘pro-Russian groups’, ‘self proclaimed Republic’ or ‘military with support from Russia.’

This conflict sensitive reporting is not only important when directly covering the war, explains Matsuka. ‘We don’t just cover matters of war and peace. The war has an influence on all areas of life. Ukraine has banned Russian books, films and TV channels. When a sportsman after a match reacted in Russian, this was interpreted as anti-patriotic with officials claiming that Russian was the language of the occupiers. But for many Ukrainians Russian is their first language. We try to reduce this kind of propaganda by showing that this is just one political view, but that our society is much bigger.’

Matsuka has also fallen prey to this propaganda as all reporting criticising the Ukrainian side is labelled as anti-patriotic. When the Institute investigated corruption in the Ukrainian military, a senior official began judicial proceedings against them, saying they were spies. ‘But this is my job as a journalist.’ Before the war even broke out, Matsuka had his apartment set on fire after an investigation into the embezzlement of public funds.

The amount of online hate speech and threats he receives has only grown since then. He produces a recent post from an anonymous blogger who has written pages and pages of text leading people to believe he is pro-Russian. ‘We don´t know where it comes from, but it could very well come from the Russian side,’ says Matsuka. In that way they can undermine his authority among Ukrainians. He gives a sad smile. ‘It is complicated.’

His work takes a high toll on his personal life. Not only does he always have to be on his guard for his own safety but, as he cannot enter the occupied territory himself because of a three year arrest warrant, he is also always concerned for the safety of the civil reporters he works with. ‘I sometimes think about my future and I don´t know if I can keep going like this. But I can´t stop either, because then I will have lost. I’ve already lost my house and home. If I quit this job I will also lose my dream of being a journalist.’

Matsuka and the group of journalists gathered in Caux will continue to exchange experiences and mutual support after their time in Caux and dedicate themselves to ethical journalism that contributes to unity and democratic values in their country.

- Find out more about Addressing Europe's Unfinished Business 2018

- Discover the new conference Tools for Changemakers 2019

By Irene de Pous