1959 – Lennart Segerstråle: ‘Art must be dangerous to evil’

By Mary Lean

04/05/2021

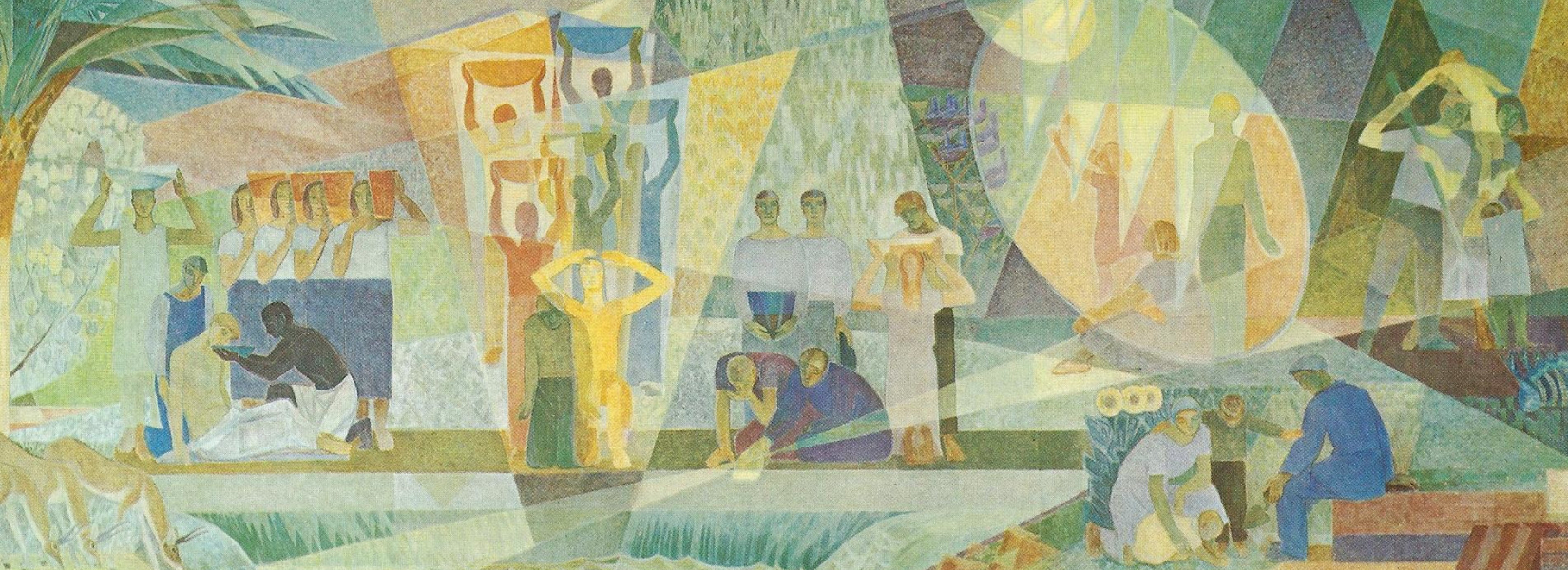

In 1959, a vast fresco – At the stream of life – was unveiled on the wall of the dining room of the Caux Palace. Its creator, the Finnish artist Lennart Segerstråle, chose the universal image of water to represent his vision of the Caux conference centre: a place where people come to the source to quench their inner thirst, and then take the water of life out to a thirsty world. In the centre, a dark figure bends to see himself mirrored in the well and rises, transformed, radiant with life.

Then aged 68, Lennart Segerstråle was Finland’s most famous animal painter, and well-known for his monumental frescos and murals. The Finnish National Gallery, which owns 105 of his works, describes the ‘juxtaposition of good and evil’ as a central theme.

‘Segerstråle’s works dealt with many of the moral issues of the post-war period, such as the problems of developing countries, racial conflicts and environmental issues,’ states their website. Segerstråle himself maintained that ‘the art of the future must be dangerous to evil’.

Just before World War II, Segerstråle had taken part in a Moral Re-Armament (now Initiatives of Change) conference in Aulanko, Finland, which had seen reconciliations between people bitterly divided by Finland’s civil war, 20 years earlier. This helped to reunite the country before Soviet Russia invaded, later that year. Segerstråle said that he painted the fresco in Caux in gratitude for what Moral Re-Armament (MRA) had done for Finland.

Among Segerstråle’s best known works are his frescos in the Bank of Finland in Helsinki and in Varkaus main church. The latter, at 242 square metres, is believed to be the largest fresco in Scandinavia.

If work on a fresco is interrupted for even a few hours, the whole section has to be redone – but he was prepared to take that risk.

An MRA friend, Paul Gundersen, visited him while he was working on it: ‘He used a scaffold on railway tracks to move back and forth along the wall. He had just interupted his work and was talking to a woman, who had come to ask for personal help. If work on a fresco is interrupted for even a few hours, the whole section has to be redone – but he was prepared to take that risk.’

In 1970, Segerstråle was one of a group of artists from many disciplines who met in Caux. The conference led to a book, New Life for Art, to which Segerstråle contributed a paper. ‘The most basic of all facts about art is that the man and the art are one person,’ he stated. Personal factors such as fear of the critics or ‘a wrong ambition’ could sap creativity: ‘there can be many enemies in me which spoil my work’.

The most basic of all facts about art is that the man and the art are one person.

He gave the example of working with a woman assistant on a church fresco. ‘One day we were trying out the colours for the next surface. We each did some, and compared them. I saw at once that my colleague’s colours were better than mine, but I decided we should go ahead with my choice. My colleague silently assented. But there was no joy in it. Teamwork did not flow. The result grew visibly worse.’ On the third day, he finally admitted his jealousy to his colleague, apologized and asked their horrified mason to resurface the wall so they could start again.

As a Christian, Segerstråle saw his art, regardless of theme, as an expression of his relationship with God. He was generous in his support of MRA, giving the fee from one of his commissions – nearly half a year’s income – for the dubbing of the film Freedom into Swahili (see 1955). Gundersen maintained that his loyalty to MRA, at a controversial time, cost Segerstråle a Presidential award.

‘Maybe it was understandable that some of those close to Lennart felt that his Christian commitment stole too much of his time,’ Gundersen wrote. ‘Lennart once told me that these critics did not grasp what was the deepest well of his inspiration.’

That well is also the focus of his fresco at Caux.

Throught the years, artists of all disciplines have been inspired by Lennart Segerstråle's concept of ‘art that is dangerous to evil’. Many of them are preparing to celebrate Caux’s 75 Years of Encounters this year. A series of arts events will be launched with an online event on 29 May. Stay tuned and watch this space for a variety of performances, artistic presentations and workshops throughout the year!

Art reflects the spirit of the times. It is a part of the present, but it also looks to the future and helps to shape it. It reports upon the fate of mankind.

Lennart Segerstråle

________________________________________________________________________

Left:

In the centre of the fresco, a figure looks into the mirror of the well of life and finds himself filled with darkness. A change takes place in his heart, and he rises, radiant with light, with his eyes open to a new world and a new life. Five figures behind him carry the living water to the five continents.

Right:

The antelopes in the foreground and the figures carrying bowls represent the millions who long to reach the well. In the foreground an African offers his bowl of water to a sick white man: a symbol of Africa bringing healing to a western world which has lost its way.

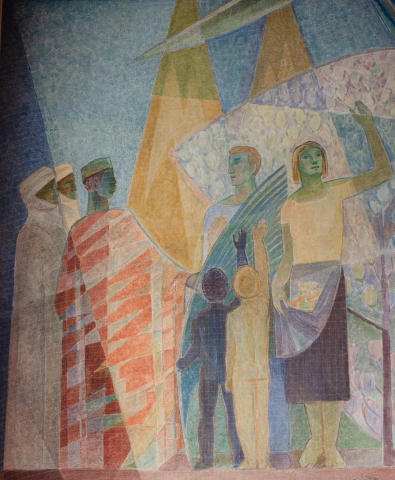

Left:

People from different races and continents stream to the water, extending their hands in reconciliation. The children hold a frond of the palm of peace.

Right:

The four snakes in the bottom right corner represent the internal enemies which poison people’s hearts. Mother and father protect their children, raising a spear to attack. They are taking a stand in the battle between good and evil, truth and falsehood.

Discover a full description of the different scenes of the fresco.

________________________________________________________________________

This story is part of our series 75 Years of Stories about individuals who found new direction and inspiration through Caux, one for each year from 1946 to 2021. If you know a story appropriate for this series, please do pass on your ideas by email to John Bond or Yara Zhgeib. If you would like to know more about the early years of Initiatives of Change and the conference centre in Caux please click here and visit the platform For A New World.

- Incorrigibly Independent, Paul Gundersen, Caux Books, 1999

- New Life for Art, Victor Sparre Grosvenor Books, 1971

- Portrait (teaser): Jan Franzon

- Photo 1970 in Caux with friends: Lars Rengfelt

- Photo top, portrait, L.S. painting fresco, with fresco: Initiatives of Change

- Photos 4 scenes: Cindy Bühler