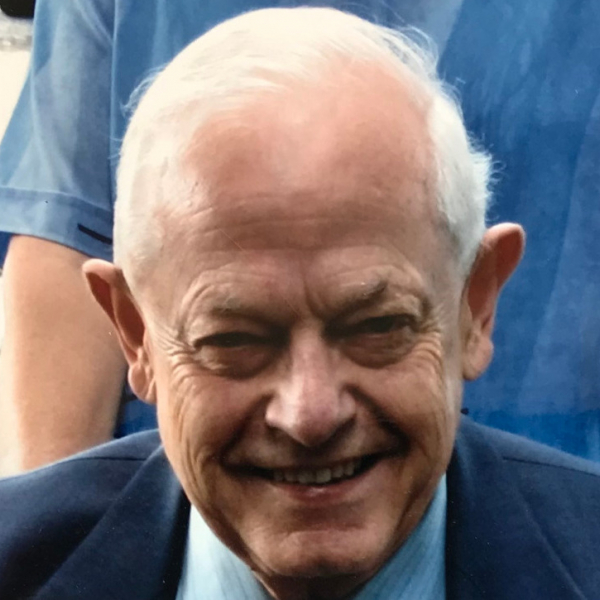

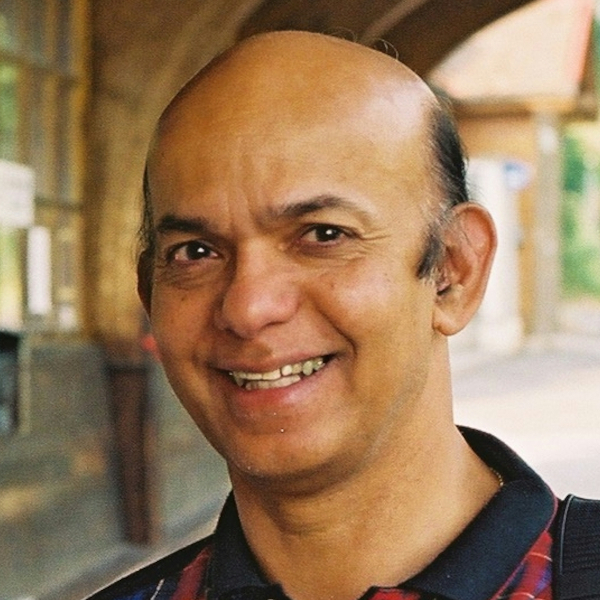

1965: Robert Carmichael - Industry which puts people first

By Andrew Stallybrass

26/05/2021

In 1965, the first freely negotiated agreement between industrialized and developing nations on the price of a raw material was signed in Rome. This pioneering accord was in large part the work of an unlikely revolutionary, who was a regular visitor to Caux in the 1950s and 60s.

Robert Carmichael was a French industrialist who believed, in the words of one observer, ‘that putting people first is the only possible way ahead for industry’. He had met Moral Re-Armament (now Initiatives of Change) just after the end of the war and put its principles into action in his factories, which processed jute for the manufacture of string, sacks and matting.

He went on to work closely with an old antagonist, Maurice Mercier (see 1951), to bring a new spirit of consultation to the French textile industry. And he felt impelled to apply this approach to the relations between industries in Europe which processed jute and the farmers in India and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) who grew it.

In 1951 Carmichael visited Calcutta, and was horrified by the misery he saw encamped on its streets. A clear thought came to him: ‘I am responsible for the millions of jute-growing peasants who are dying of hunger.’ He accepted this responsibility as a vocation and went into action.

He accepted this responsibility as a vocation and went into action.

The first step was to form an association of all the European importers of jute. Carmichael became its president. At its annual conference in 1959, he said, ‘If the European jute industry makes an effort to create a sane economy in this sector with India and Pakistan, it can find its real reason for existence. To do this, the basic motives of European industrialists must undergo a fundamental change.’

This did not go down well, and Carmichael offered to resign. When his opponents could not agree on a successor, he was asked to resume his position.

In spite of increasingly disabling arthritis, Carmichael travelled back and forth to Asia, weaving new ties between India and Pakistan and the eight European jute-importing countries. His task was exacerbated by speculative traders and by the ongoing hostilities between India and Pakistan.

In 1965 all the countries which produced or processed jute met in Rome, under the auspices of the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. Several delegations arrived with instructions which would have made a conclusion impossible, and Carmichael’s European colleagues did not want him to commit himself to one side or the other.

For years Carmichael had been building personal friendships with each of the men at the conference. This helped him to overcome the obstacles. He offered the chairmanship of the debate to the most awkward person. Astonished and flattered, this man accepted the responsibility of arbiter, and carried out his duties impeccably without imposing his own arguments.

Carmichael had introduced such a spirit of frankness, that one of the Asian delegates proposed a figure which was agreed immediately.

In friendly conversation with another man, Carmichael discovered the parties agreed more than their official instructions allowed them to reveal.

Everyone expected that the figures put on the table at the start would be so far apart that agreement would be impossible. However, Carmichael had introduced such a spirit of frankness, that one of the Asian delegates proposed a figure which was agreed immediately. The other details then settled themselves as a matter of course.

For the first time the price of a basic raw material had been freely negotiated between equal partners. This showed that a similar approach to other international trade negotiations was possible.

There’s a footnote to this story. Early on in Carmichael’s connection with MRA, a friend had challenged his busy lifestyle. He pointed that as a conscientious Christian, Carmichael would of course consciously resist if the devil tried to tempt him with any obvious sins. But instead, this friend suggested, the devil might fill his life with so many ‘good works’ that he’d miss the task that God most wanted him to fulfil. In response, Carmichael resigned a number of roles, and told his wife that he felt naked. But when the agreement was reached in 1965, he saw the fruits of this painful stripping away.

Adapted from 'The World at the Turning', by Michel Sentis and Charles Piguet

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Watch Robert Carmichael in an extract from our archives from the silent film "Ciné Journal Suisse 1953 (00'52" - end)

_______________________________________________________________________________________

This story is part of our series 75 Years of Stories about individuals who found new direction and inspiration through Caux, one for each year from 1946 to 2021. If you know a story appropriate for this series, please do pass on your ideas by email to John Bond or Yara Zhgeib. If you would like to know more about the early years of Initiatives of Change and the conference centre in Caux please click here and visit the platform For A New World.

- Photos: Par lui-même, Robert Carmichael, 1975, Caux Books and Initiatives of Change

- Film: Ciné Journal Suisse 1953, Initiatiatives of Change

- An unexpected revolutionary, Donald Simpson, The Industrial Pioneer, 1984